Please, allow me to indulge myself. Let me tell you a tale about a book, a film, a series of video games and what is perhaps the world’s eeriest man made disaster area. I’ll even throw in a bit of media theory. Let me tell you about the Zone of Alienation.

Following the explosion at the Chernobyl nuclear reactor station in 1986, a 30 km exclusion zone was established around the plant to ease the evacuation of civilians and prevent others from entering the highly contaminated area. Despite being a horrible example of technology gone awry, this Zone of Alienation, as it’s come to be called, has acquired almost mythical properties. Mankind attempted to control a mysterious, invisible force and failed. The crumbling architecture and abandoned machinery bare silent witness to this failure even today. As a tale of human hubris, it bears a striking resemblance to the story of Icarus’ burned wings, only with less feathers and more concrete. One can even go so far as to say that the Zone as a whole is a direct manifestation and perhaps permanent reminder of the failed Communist experiment.

Though it might seem obvious that the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone is a fertile breeding ground for the imagination, the idea of an invisible, unknowable force infecting the land already resonated within the former Soviet Union. The 1972 science-fiction novel Roadside Picnic, written by Boris and Arkady Strugatsky, describes the existence of a mysterious quarantine zone. An area where the normal laws of physics seem warped and sometimes completely broken. Most likely extra-terrestrial in nature, this zone is filled with strange objects and materials utterly alien to mankind. Though cordoned off by the military and regularly examined by researchers, the zone is also routinely raided by ‘stalkers,’ desperate individuals who crawl through the zone’s muck, hunting for alien artifacts and hoping to sell them on the thriving black market. Though the zone still bears traces of human habitation – abandoned houses, factories, railways – it has become something else entirely. The land itself has become poisoned and lethal. Like ants and forest animals confronted with the remnants of a roadside picnic, mankind simply cannot fathom what has taken place inside the zone. As with the real Chernobyl Zone of Alienation, the zone described by the Strugatsky’s was seen by some as a metaphor for the entire Communist system. A system that had proven to be hazardous to its people as well as its lands.

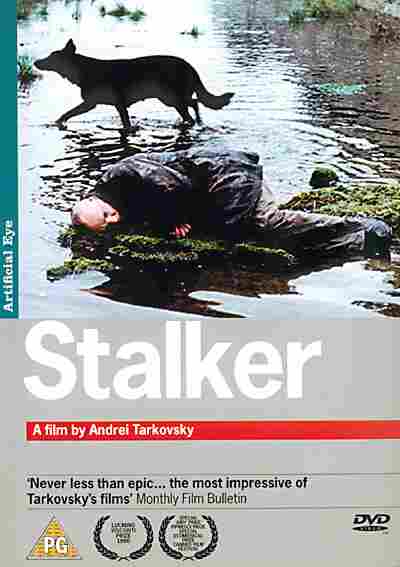

The story doesn’t end here, though. In 1979 Andrei Tarkovsky directed a movie called Stalker. Loosely based on Roadside Picnic, the movie tells the tale of a stalker as he guides a professor and a writer through a mysterious zone. Tarkovsky’s presentation of the zone is strikingly minimalist. Long, meandering takes that pan across the still landscape, sparse dialogue and an atmospheric musical score lend the movie an otherworldly feel. The zone’s deadly anomalies are never actually seen, but the ruined industrial landscape combined with the stalker’s reverence for its power make the zone feel authentic. This is an area that can break a man if he doesn’t obey its rules and treats it with respect. The danger is real. Over the years many rumours have surfaced pertaining to the actual locations depicted in the movie. Some said that it was actually filmed in the areas surrounding the real Chernobyl plant. The movie, however, was shot on location in Estonia. In a curious blend of reality and fiction, the film reels containing the first version of the film were destroyed due to the dangerous chemicals that saturated the area. The film crew themselves were also effected. Many experienced illness and even cancer due to their time spent filming on location. Like the fictional stalkers, they had risked too much and the zone had changed them.

The actual event of the 1986 Chernobyl disaster is still felt throughout the modern day Ukraine and Belarus. Confronted with the Zone of Alienation, nearby inhabitants reached out towards the compelling stories of the fictional zones depicted by the Strugatsky’s and Tarkovsky. Soon, real life stalkers ventured inside the Chernobyl exclusion zone risking health and freedom to loot whatever valuables were left behind during the evacuation.

The mythology surrounding the Zone of Alienation, already as vibrant as, say, that of Area-51, received a new impulse in 2007 with the release of the computer game S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadows of Chernobyl by GSC Game World. This game fuses the fictional zones of Roadside Picnic and Stalker with the myths and locale of the actual Chernobyl exclusion zone. Presented as a first-person shooter, the player assumes the role of a stalker and hunts for artifacts, fights mutant wildlife and explores derelict military-industrial complexes. Consisting of three separate games at this moment, the series depicts the Chernobyl Zone of Alienation as a highly atmospheric, desolate area filled with dangers both visible and invisible. Spending the night in a ruined factory complex, huddled around a campfire gives a real sense of adventure, despair and ever present danger. Another example of fiction bleeding into reality are the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. cosplay events where fans dress up in a mix of disheveled military gear and home-made sci-fi equipment and battle each other across outdoor areas.

To add a little theory to this hopefully entertaining yet otherwise light piece, I’d like to call upon the remediation and premediation theories presented by Bolter & Grusin and Grusin respectively. Remediation theory is based on the concept that one medium can be represented inside another medium. Of particular interest is the idea that “remediation… reform[s] reality itself.” Starting chronologically, the movie Stalker is a remediation of the book Roadside Picnic. Not so much because it cinematically represents the book itself, but because it remediates its fictional reality. Together, both the book and the movie premediate the creation of the actual Chernobyl Zone of Alienation. This might seem odd, but is in line with Grusin’s theory which states that “the logic of premediation…insists that the future itself is also already mediated.” A more radical standpoint would be to say that the Chernobyl event was actually a remediation of the book and movie, because it reformed reality itself according to their fictions. The next step in this chain of remediation events is the creation of the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. computer games. In its fictional depiction of the Chernobyl zone, the series remediates both the book and movie, but also the actual Zone of Alienation. Because the games are set in the near future, who knows, they might even be premediations of a future yet to unveil itself. Other examples of remediation include the real-life Chernobyl stalkers adopting the ‘stalker’ moniker and customs and the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. cosplay events.

If all this talk of reality warping zones and stalking has peaked your interest, perhaps you should look into taking a guided tour of the actual Chernobyl area. I’m not kidding, this is actually possible. If you prefer a less intense introduction to the zone and its wonders, maybe you should start by reading the book, watching the movie and playing some of the games. I highly recommend them. Be careful not to stare into the zone too deeply, though. It might look back.

This post was inspired by Jim Rossignol’s post on BLDGBLOG, which is a wonderful website with an out-of-the-box approach to architecture.

Literature

Bolter, Jay David and Grusin, Richard. “Remediation.” Configurations 4.3 (1996): 311 – 358. Print.

Grusin, Richard. “Premediation.” Criticism 46.1 (2004): 17 -39. Print.